|

Photo: Institute of Marine Research/FIS

Chasing Shadows: Tracking Europe’s Top Predatory Fish Across Borders

NORWAY

NORWAY

Monday, April 21, 2025, 00:10 (GMT + 9)

How scientists, students, and fishermen are uncovering the secret journeys of cod, sea trout, and sea bass to protect marine life in a changing ocean.

Tracking Europe’s Predatory Fish on the Move

In the MOVE project, researchers, students, fisheries managers, and fishermen are working together to understand how large predatory fish use coastal ecosystems—and what it takes to effectively protect them. By combining fish tracking technology with ecosystem management, the project is setting new standards for sustainable marine conservation.

.png) At the heart of MOVE is a network of acoustic receivers and tagged fish, allowing scientists to monitor the movements of cod, sea trout, and sea bass along the Norwegian coast—and potentially all the way across Europe. By mapping these underwater journeys and overlaying them with data on marine protected areas (MPAs), habitat use, and human activity, the project is building detailed "movescapes" that reveal how, when, and where fish travel. At the heart of MOVE is a network of acoustic receivers and tagged fish, allowing scientists to monitor the movements of cod, sea trout, and sea bass along the Norwegian coast—and potentially all the way across Europe. By mapping these underwater journeys and overlaying them with data on marine protected areas (MPAs), habitat use, and human activity, the project is building detailed "movescapes" that reveal how, when, and where fish travel.

“The goal in Norway is to track key predator species in Raet National Park to see how they use the coastline—and to find out if human activity is disrupting their natural behavior,” explains Erlend Astad Lorentzen of the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (HI).

Cross-Continent Fish Tracking

If any of the tagged fish swim off toward the Norwegian Trough—or even as far as Portugal—researchers will know.

“We’ve tagged a variety of species with acoustic transmitters that are picked up by listening buoys in Raet and the surrounding sea,” says researcher Inge Elise van der Knaap. “But if one of our fish swims past similar buoys elsewhere in Europe, we get that data too.” “We’ve tagged a variety of species with acoustic transmitters that are picked up by listening buoys in Raet and the surrounding sea,” says researcher Inge Elise van der Knaap. “But if one of our fish swims past similar buoys elsewhere in Europe, we get that data too.”

That’s especially relevant for the 12 sea bass tagged near Tromøya in Arendal last autumn.

“Sea bass have established themselves in southern Norway, but we still know little about their seasonal behavior,” van der Knaap adds. “They're caught mostly in summer—but we don’t yet know if they head south for winter, or just hang out in deeper water.”

Weekend Trips and Coastal Journeys

Previous research with acoustic tags in fjords has shown that many cod are quite stationary—until they suddenly aren’t.

“Sometimes fjord cod vanish from our monitoring network for a few days, then reappear. We don’t yet know where they’ve gone or what they’re doing,” says van der Knaap.

To close these knowledge gaps, MOVE has extended the reach of its listening buoys into the Skagerrak and North Sea, including the slope of the Norwegian Trough, where predatory fish often make unexpected excursions.

“Cod have been recorded swimming more than 40 kilometers offshore, diving as deep as 400 meters—crossing areas with heavy fishing activity,” van der Knaap says. “It’s incredibly interesting.”

What This Means for Marine Protection

This research has critical implications for marine protected areas. If cod, for example, are leaving protected zones to swim through heavily fished waters, current conservation measures might not be enough. This research has critical implications for marine protected areas. If cod, for example, are leaving protected zones to swim through heavily fished waters, current conservation measures might not be enough.

“The aim of an MPA might be to safeguard a species like cod,” van der Knaap notes. “But if they regularly exit these areas, their protection becomes more complex.”

In just one year of tracking, surprising patterns have emerged. One example is the behavior of pollack (lyr), which has shown a tendency to patrol large stretches of coastline in rhythmic cycles—often diving to unexpected depths of 60 meters and returning to the same spots after several days.

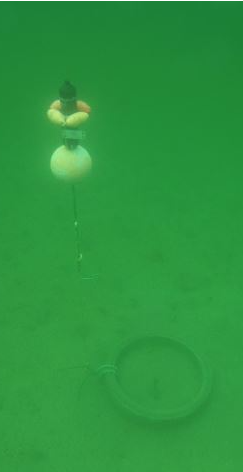

Telemetry rig used to map fish movements. Photo: Institute of Marine Research (Havforskningsinstituttet) -->

Next, the MOVE team aims to map the specific risks these fish face during their travels—from fishing activity to habitat disruption.

Looking Ahead

MOVE will continue expanding its network of listening buoys in the North Sea, particularly in areas being considered for offshore wind power development. Researchers also plan to tag additional fish and study their migrations over the coming years.

“We’re only scratching the surface of how these species interact with their environment,” says van der Knaap. “This data will be crucial in shaping future marine policies and conservation strategies.”

[email protected]

www.seafood.media

|